This blog post was written by UHI Institute for Northern Studies MLitt Viking Studies student, Stephen Barnaby.

I grew up in Thurso, surrounded by streets named after luminaries from the days of the northern Norse jarldoms: Sigurd, Thorfinn, Sweyn, Harold, Magnus. I’d like to claim these dated from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but they consisted of pebble-dashed and faux-Scandinavian wooden-fronted semi-detached houses, built in the 1950s to house those coming up (and, I’m guessing, it was always ‘up’) to work at the newly constructed fast reactor Dounreay.

My father was one of these migrants – that’s right, I’m from a nuclear family – although we came somewhat later, and did not live in a Norse-named street. We had, though, a wonderful view – on rare, haar-less days – of the isle the Norse named Háey, Hoy, ‘high island’, due to its distinctly un-Orcadian loftiness. Not until fifty years after our original move did I actually get the chance to visit there and experience that remarkable phenomenon whereby it can be July in the rest of Orkney but December in Hoy.

Still, those street names give a flavour of Caithness’ attachment to its Norse heritage. After all, they were not named by an ‘Atomicker’ – as the incoming nuclear hordes were known – but by Reay-born Donald Carmichael, Dounreay’s first general secretary. The northeast of Caithness, in particular, abounds with placenames of Norse origin. These include those traditional sworn enemies Wick, from vík, ‘inlet or bay’, and my old hometown Thurso, from from Þórsá, literally ‘Þórr’s River’’, although debate remains over whether this was actually either Þjórsá, ‘bull’s river’, or else a ‘Norse-ification’ of an extant Pictish name, particularly given that the Norse apparently called Thurso River skínandi, ‘the shining one’. The latter is now the name of a night-club in Thurso, which I can personally verify does not date back to viking times.

Many Caithness dialect words derive from Norse. I will always associate one of these, ‘scorie’, from skári, ‘young gull’ with hearing gunshots at Wick airport and being assured by a taxi driver ‘ey’re jist scaring e scories off e runway’. This tendency in Caithness dialect to drop the ‘th’ from definite articles and pronouns presumably did not derive from the Norse, fond as they were of their eths (ð) and thorns (Þ).

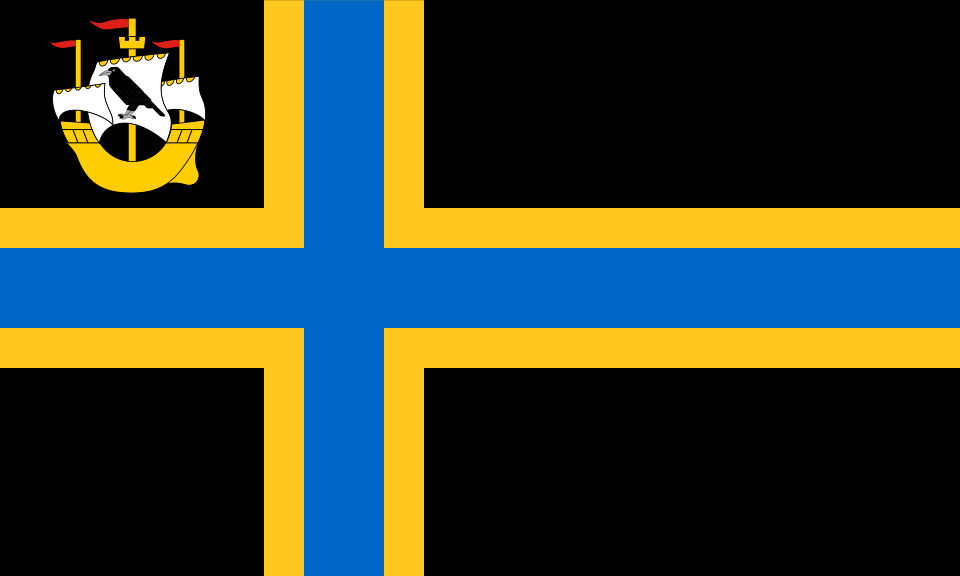

I should say that, in recent years, this pride in Caithness’ Norse past has grown yet further, with the unveiling in January 2016 of a Scandinavian-style flag representing the county, complete with skewed Nordic cross. What is more, that summer saw Caithness staging a Viking Festival, with a viking village established in those Thurso playing fields known locally as the Dammies, hosting battle reenactments, crafts and feasting.

Amidst all of these rollicking re-inventions of the days of the jarldoms, though, something has long been lost: a sense of local folk memory, of stories that have been passed down through the centuries, sometimes possibly being distorted, Chinese-whispers style, growing arms and legs, or, perhaps, originating from fantasy in the first place. There is, though, the tantalising possibility that such tales may sometimes reveals truths or incidents not featured in the ‘elite-centred’ medieval Scottish and English chronicles or, by far our most important written source, the thirteenth-century Icelandic history of the jarls later misleadingly dubbed Orkneyinga Saga: ‘the story of the Orkney people’.

There were fascinating hints of this in the writings from around 1780 of the Reverend Alexander Pope of Reay; also, in those from 1861 of another Caithness author, James T. Calder. Both reported the common belief that various standing stones – which we now know to have been almost certainly erected in neolithic times – commemorated the death sites of Norse worthies. One of these, in the parish of Bower, is still known as Stone Lud. Calder and Pope recorded its name as being popularly connected with that of Jarl Ljótr, depicted in Orkneyinga Saga as falling in Caithness while battling the forces of his brother and jarldom rival, Skúli.

Also evidently still strong in the 1780s and 1860s was the belief that the late twelfth and early thirteenth-century jarl Haraldr Maddadðarson had been ‘wicked Earl Harold’, the ‘scourge of Caithness’. He famously, c.1201, had bishop John of Caithness mutilated outside Scrabster Castle, half a mile from where I grew up, marked now only by a modern triangular sculpture. Haraldr apparently thought John was sowing discord between him and King William of Scotland. Indeed, Bishop of Caithness was evidently a perilous posting around this time. In 1222 John’s successor Adam was burned alive in his house at Halkirk (from Norse Hákirkja, ‘high church’) by farmers angry at a sharp increase in the amount of butter they were required to pay as tithe. The jarl, Haraldr’s son Jón, had apparently refused to intervene in the dispute. However, Pope and Calder cited local tradition that Jón uttered comments – unrecorded in sagas or chronicles – whose irritated tone was misinterpreted by the mob, Henry II/Thomas Beckett style: “The devil take the bishop and his butter; you may roast him if you please!”

Also entertaining is Pope’s report that local folk believed Claredon Hill, near Thurso, to be the site of the battle between the forces of ‘wicked’ Jarl Haraldr and his namesake jarldom candidate Haraldr ungi, ‘the younger’, and that its name derived from shouts of ‘Clear the Dane!’ heard during the struggle. Quite why combatants would have been speaking modern English is unclear. Similarly inexplicable would be their anachronistic reference to ‘Danes’: the heritage of both Haraldrs was probably a combination of Scottish Gaelic with their ancestral Norse Norwegian. Indeed, while jarls needed the permission of the Scottish king to rule in Caithness, Norwegian royal consent was required to govern Orkney and Shetland. However, by Pope’s day, ‘Danes’ had long been the catch-all term for the invading incomers, prefiguring ‘vikings’ – and, it’s tempting to add, ‘Atomickers’.

On this latter theme, particularly remarkable was the account of a genuine Dane, J.J.A. Worsaae, of his travels to Caithness and Sutherland in 1846/47. This was part of a UK-wide mission on behalf of King Christian VIII of Denmark to enquire into monuments and memorials concerning Danes and Norwegians (Norway at that time was ruled by Denmark). In the days of the jarldoms, Sutherland was part of Caithness; a distinct part, too, as was indicated by its originally Norse name Suðrland, ‘southern land’. (The idea that anywhere in the region was ‘southern’ would have come as news to my parents. They thought they’d arrived in the Arctic).

Sutherland had a stronger Gaelic tradition, both in the time of the jarldoms and in the nineteenth century. Consequently, in northeast Caithness, Worsaae found plenty of Norse-derived personal and place names to stoke his pro-Nordic bias, leading him to declare the locals taller, fairer and more nautically skilled than the Sutherlanders. Also, like Pope and Calder, he encountered the common popular association of standing stones with fallen Danish nobles. However, in Sutherland he reported that, among the ‘poorer classes’ in Gaelic-speaking areas, were ‘numberless traditions’ regarding the cruel ‘levying of provisions by “The Danes”’. Also, although locals pointed out numerous barrows and cairns believed to be the burial sites of ‘Danish’ nobles, the emphasis was placed less on their nobility, and more on their deaths at the hands of righteously rebellious Sutherlanders. Rather astoundingly, Worsaae reported that his guide was often asked by villagers not to show him around, because they genuinely believed he was on a reconnaissance mission to prepare the way for a second Danish invasion. Indeed, on several occasions, when leaving a village, Worsaae saw old people ‘wring their hands in despair’.

One notion that both Sutherlanders and northeast Caithness folk apparently shared, though, was that the ‘Danes’ had invented practically everything, ranging from hand querns, or hand mills to….. bagpipes! It was also believed that they had introduced the burning of turf, fascinatingly redolent of Orkneyinga Saga’s erroneous claim that the Norse were the first in Scotland to dig peat for fuel, a possible example of an idea enduring in folk memory for centuries.

This local attribution of inventive genius to the Norse evaporated into the ether long ago. What is more, I strongly suspect that the fear of imminent Danish invasions has subsided somewhat in modern-day Sutherland. However, the concept of Caithness’ supposedly heroic Norse heritage, so appealing to Worsaae in the 1840s, seems to be alive and well today.

A final word of warning, though, about possible downsides to this Nordic love affair. There is an element in Caithness that detests any suggestion – despite the wealth of supporting evidence – of the county ever having had the remotest semblance of a Gaelic culture. This was perhaps expressed in the most literal and alarming way in September 2013, when an information sign near Wick Airport, which included Gaelic translations, had bullets shot through it.

Then again, were I to clutch at straws, I could suggest a more innocent explanation for this apparent display of wantonly aggressive prejudice:

Ey might jist have been scaring e scories off e runway.

The header photograph shows the sculpture that marks the site of Scrabster Castle near where Bishop John was mutilated. Source: Stephen Barnaby

If you would like to join UHI Institute for Northern Studies as a student contact us on ins@uhi.ac.uk

Leave a comment