Professor Judith Jesch, Dr Matthew Blake, Judith Jesch and Corinna Rayner of the University of Nottingham talk to us about their latest research in this guest blog post.

Ragna’s Islands is an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research project built around a new translation of The Saga of the Earls of Orkney (also known as Orkneyinga Saga) by Judith Jesch and due for publication in 2025. It will bring together evidence of archaeology and place-names to transform our understanding of the Viking and Norse periods in northern Scotland by integrating recent and current archaeological and work into the new translation.

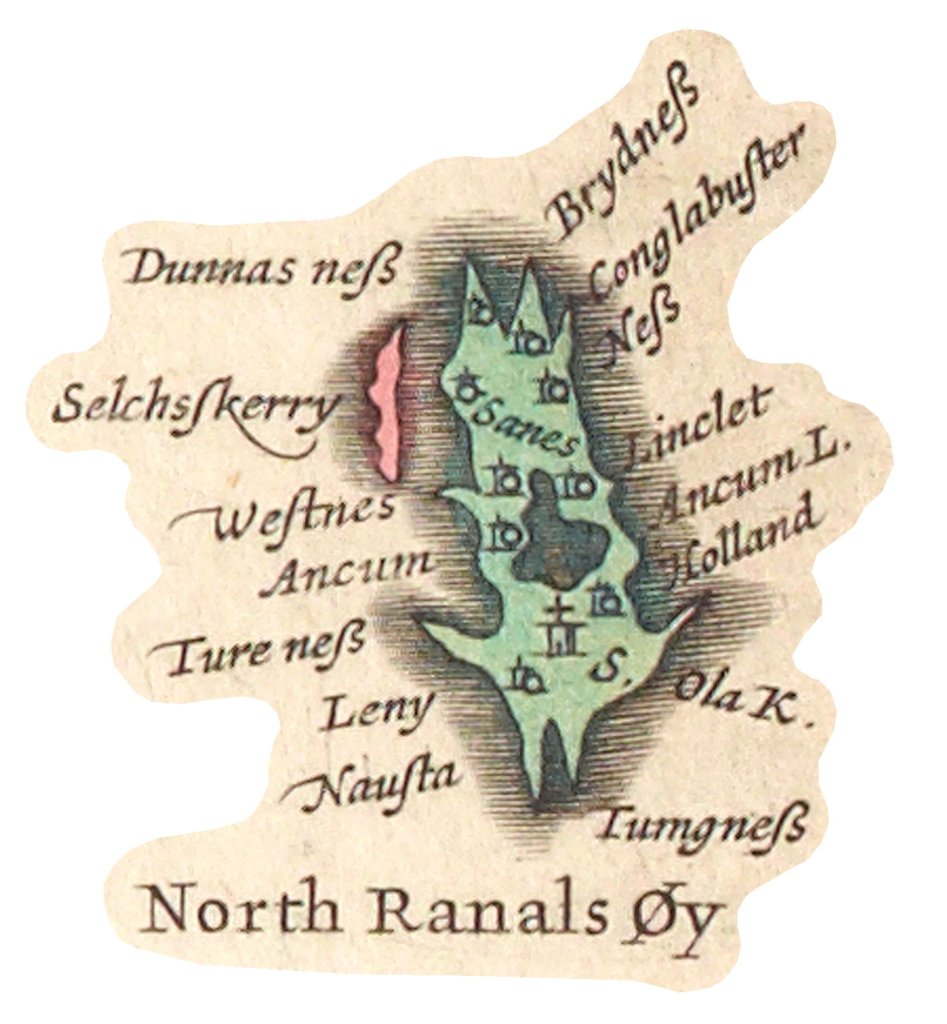

Research has been ongoing into the place-names mentioned in the saga as well as the place-names of Fair Isle (Shetland), and Papay and North Ronaldsay (Orkney) led by Corinna Rayner and Dr. Matthew Blake. These three islands were chosen because they are linked in one way or another in the saga, whether by Ragna herself since she held estates in North Ronaldsay and Papay, or by the beacon system that operated between Fair Isle and Orkney in the Norse period, which involved Ragna’s son Þorsteinn. The place-names we are looking at were often coined in the Viking/Norse period and so interpreting them is invaluable for understanding that period, the landscape and the activities of the people that lived there.

The project started in February 2024 and we have been ably assisted by volunteers and contributors across the three islands, Orkney and beyond. In addition to the annotated translation we will be creating exhibition content and booklets for each islands’ heritage venue highlighting their place-names and their Viking past.

The importance of spelling and pronunciation

When talking with islanders about their places, we were told many times that the way they are said locally often varies greatly from the ‘authoritative’ spellings on maps such as the Ordnance Survey. Spellings are key to our understanding of place-names which themselves are made up of descriptive elements meaningful when coined. We quickly learned that spellings on maps and in official documents needed to be treated with caution.

The pronunciation of place-names can also retain important information about their meanings and an important part of the project has been to record how the place-names of each island are pronounced locally.

The Importance of Listening

We were struck, in Papay, in Fair Isle and in North Ronaldsay by just how important the pronunciation of place-names was to local people. There was a sense that this knowledge of how to say things correctly was under threat. More than once we were asked how we planned to spell the place-names, because as far as some islanders were concerned no one has gotten it right. Another comment was that the English alphabet does not have the letters needed to represent the sounds in place-names. Dialect, however, is very difficult to spell, and so our way around this has been to record and collect islanders’ pronunciations of their names for addition to the database we are building, so that researchers can use those pronunciations to determine, where possible, the elements making up those names.

Old Names, New Meanings?

Further project activities include the various events and activities we have held in schools, the talks and community walks held in the islands and our growing selection of blogposts. Amongst other saga-related things, the Ragna’s islands blogspot is where we examine the place-names of the saga and the three chosen islands. We have guest bloggers, archaeologists and students looking at the place-names. There is plenty to read now and more in the offing. We’re particularly interested in how the place-names, together with archaeological and archival evidence and the context that the saga provides, can help us to locate places, not only geographically, but also in terms of how the landscape of Orkney was understood and used in the Norse period.

Sword-storms and Much Much More

Venturing into the sea, we consider the location of what a stanza in the saga describes as ‘the sword-storm off Rauðabjǫrg’. Our aim was to locate the battle site, where was it? The options discussed include Dunnet Head in Caithness, Roeberry in South Ronaldsay, a Stroma headland called Red Head, and Roberry in South Walls, Hoy. The meaning, deriving from ON bjarg ‘hill, cliff, crag’ and ON rauðr ‘red, reddish, blood red’ giving ‘red cliffs’, doesn’t help narrow the location down very much – so it is the saga evidence once again that we turn to! In the end we opt for Roberry in South Walls, but to find out why you’ll have to read the blogpost.

We have discussed the derivation of island names, such as Swona, the question was whether it was named after a Viking called Sveinn or can a more prosaic solution be found, was the island of Swona, where wild cattle now roam, once known for its pigs? We ask: Who were the Papar of Papay? and along the way discuss Vikings, monsters and the life of St. Findan (also known as Fintan, d.878) an Irish saint, sold into slavery who escaped the clutches of the Vikings whilst in Orkney. We tell the tale of Ragna of and her ‘red headdress made of horsehair’ and wonder, just what were the ‘eyebrows’ of Damsay.

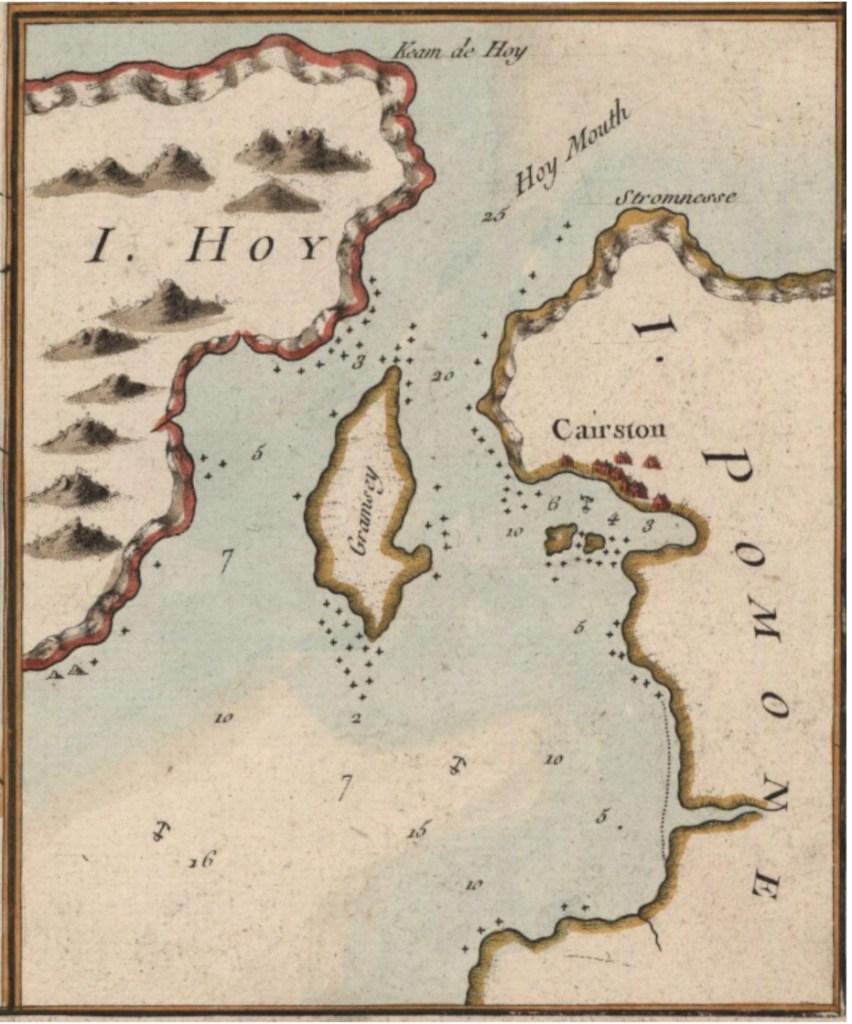

In our Knarston blogpost we weigh up the possible elements present in the name (a personal-name or a boat-name in knǫrr and whether the second element is staðr or stǫð); we turn to the manuscripts themselves looking for palaeographical clues and consider the influence scribes will have had on what we see today, and, we visit the place to look at the appropriateness of the name in the landscape together with other place-names like Scapa!

On balance, we settle for a ‘the place with war/trading ship landing stances’ interpretation which fits nicely with our forthcoming Scapa blog… watch this space!

In our Cairston blog, another staðr/stǫð name, we think about the strategic positioning of the place. We consider its importance as a landing-place using a variety of sources, as well as the saga and etymology, including historical maps, the Ordnance Survey name books and archives held in Orkney Library to consider why this place-name was significant enough to give its name to an earl’s estate.

Please do pop on over to the Ragna’s Islands blogspot to find out more, and if you want to get in touch with Professor Judith Jesch, Dr Matthew Blake and Corinna Rayner, please do, they would like to know what you think!

Thanks to Matthew Blake, Judith Jesch and Corinna Rayner.

Leave a comment